I became an evangelical Christian while in college in the nineties. Most of what I knew about Christianity came from what I learned at the megachurch I attended, from InterVarsity Christian Fellowship at OSU, from my first read of the Bible from start to end, and from Christian radio. I did not realize how modern of a phenomenon evangelical Christianity was. In my view, evangelicals were recovering the “biblical” Christianity that had been lost through the legalism or liberalism of past generations of Christianity.

Evangelicalism was also simple. We were told what to believe about debated theological issues, difficult ethical questions, or hot political topics. It’s not that preachers commanded us to believe these things. It was the culture of evangelicalism. We all thought the same, voted the same, and saw the same issues as central to the gospel.

It wasn’t until after I earned my doctorate in theological studies at an evangelical seminary that I started to realize how different the biblical world was from the modern evangelical world and how different we think today about theological, political, and ethical issues than Jesus or Paul did. This has caused me in recent years to revisit the foundation that my faith was laid upon in the nineties.

One fundamental issue that I have rethought heavily over the years is our understanding of the basic gospel message. I wrote about this in my article “The Biblical Gospel vs. the Evangelical Gospel,” where I noted that the Gospels don’t present what we think of as “the gospel,” and I demonstrated that “the gospel” according to the biblical authors was centered on God’s kingdom coming to earth, not on how to go to heaven when you die, a topic that is rarely addressed in the Bible.

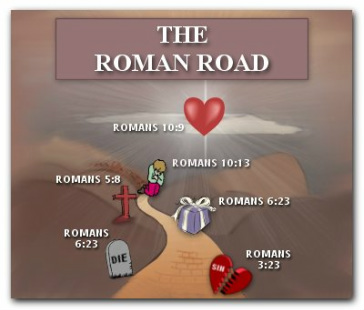

In this post I want to do something similar, but instead of focusing on the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, I want to look at the book of Romans and particularly the idea that Romans gives us a roadmap to salvation, commonly referred to as “the Romans Road,” a series of verses isolated from their context by the Baptist preacher Jack Hyles in 1948. I want to demonstrate that Romans is addressing an entirely different question and that the popular use of Romans to teach someone how they can go to heaven when they die is a misuse of Scripture that makes the Bible serve our theology rather than uses the Bible to teach us theology.

The “Romans Road”

One of the ways I was taught in the nineties to explain my faith was to walk people through Paul’s teachings in Romans. According to this teaching, there were four basic ideas in Romans that needed to be highlighted:

- We are all sinners, who have displeased God: “All have sinned and fall short of the glory of God” (Romans 3:23, ESV; cf. Romans 3:10)

- We deserve the judgment of death and hell: “For the wages of sin is death, but the free gift of God is eternal life in Christ Jesus our Lord” (Romans 6:23, ESV)

- God has freely offered heaven instead of hell: “God shows his love for us in that while we were still sinners, Christ died for us” (Romans 5:8, ESV)

- In order to experience this, we must make a confession of faith: “because, if you confess with your mouth that Jesus is Lord and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved. For with the heart one believes and is justified, and with the mouth one confesses and is saved.… For everyone who calls on the name of the Lord will be saved.” (Romans 10:9-10, 13, ESV)

This is such a simple and memorable way to present the gospel that it has been used extensively and has become our very definition of what “the gospel” means: we sinners can escape hell and go to heaven by believing in Jesus. The problem is that this is not at all how Paul defines the gospel in Romans and that each of the passages here is taken out of context to get this interpretation of the gospel.

“The Gospel” According to Paul

Paul defines “the gospel” right at the beginning of Romans. Not surprisingly, his definition is close to Jesus’s definition. I noted in “The Biblical Gospel vs. the Evangelical Gospel” that Jesus repeatedly defines the gospel as being about God’s reign being established on earth, not about what happens to an individual when they die. From Jesus’s first words, he preached, “The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God has come near; repent, and believe in the gospel” (Mark 1:14-15). The good news is that God’s reign is beginning. This is also what he taught the disciples to preach: “the kingdom of heaven is at hand” (Matthew 10:7). Repeatedly Jesus’s teaching is summarized as being “the gospel of the kingdom” (Matt 4:23; 9:35; 24:14; Luke 4:43; 8:1; 16:16; cf. John 3:3, 5). The gospel, or “good news,” is not what happens when you die, but that in Jesus God is dethroning Satan and taking over the rule of earth.

This is also what Paul says at the beginning of Romans:

Paul, a servant of Christ Jesus, called to be an apostle and set apart for the gospel of God—the gospel he promised beforehand through his prophets in the Holy Scriptures regarding his Son, who as to his earthly life was a descendant of David, and who through the Spirit of holiness was appointed the Son of God in power by his resurrection from the dead: Jesus Christ our Lord. [Romans 1:1-4, NIV]

Paul is introducing himself here as someone who was “set apart for the gospel of God.” This gives him an opportunity to explain what that gospel is: it is a gospel “regarding his Son.” What does it say about the Son? He has earthly royal pedigree (“a descendant of David”), but he has also been appointed as the agent of God’s rule in heavenly places by being raised from the dead. “Son of God” is a royal title. Kings from Egypt to Rome claimed divine authority to reign on earth by being the son of God.

(Interestingly, translators have had trouble with the word “appointed” in Romans 1:4. Other versions use the word “declared” for fear of giving the impression that Jesus was not Son of God until the resurrection, but the Greek word here does not mean “declared” and is regularly translated “appointed” elsewhere. The KJV used the word “declared” and modern translations have generally followed suit. The 2011 revision of the NIV bucked this trend and went with the more accurate translation, “appointed.”)

So in Romans 1:3-4, Paul takes two verses to summarize the gospel, and he summarizes it as being about Jesus’s enthronement as Son of God in power. There is nothing here about what happens when you die or about making a decision of faith. The good news is that Jesus has now been appointed the true ruler of the earth. Caesar’s actions from Rome are not what decides things throughout the world, but Jesus’s actions from heaven do. This is the good news: it is the gospel of the kingdom. God has taken the throne in Jesus.

It is true that the next two verses in Romans (Romans 1:5-6) call people to belong to Jesus, and Romans 1:16 specifically addresses the salvation that comes through the gospel. But salvation is what happens because the gospel is true: because Jesus has taken the throne, those who trust in him will experience the blessings of the kingdom. Our salvation is not the good news itself; it is one of the side effects of the good news that God is taking charge of the earth.

Salvation in Romans

The fact that Romans 1:16 mentions “salvation” indicates that Paul does have something to say in Romans about “being saved,” but it is not what modern interpreters think. Hell is never mentioned or even hinted at in Romans. Salvation in Romans 1:16 is from the wrath of God that is being revealed “on earth” in Romans 1:18. Repeatedly Paul mentions the judgment of God that people experience:

- “they became futile in their thinking, and their foolish hearts were darkened” (Romans 1:21),

- “God gave them up in the lusts of their hearts to impurity, to the dishonoring of their bodies among themselves” (Romans 1:24),

- “God gave them up to dishonorable passions” (Romans 1:26),

- “God gave them up to a debased mind to do what ought not to be done” (Romans 1:28).

All these things lead to death (Romans 1:32), but because Jesus overcame death and is enthroned over death and all hostile forces, we can experience life everlasting. And not only that, but it is a different life than the one described in the bullet points above. We can “be transformed by the renewal of [our] mind” and offer our bodies “as a living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to God” (Romans 12:1-2). This is what salvation is: no longer living according to the flesh, but living according to the Spirit (Romans 6-7).

By making Romans about how to go to heaven when you die or about how to escape hell, we read the word “salvation” and hear something very different than what Paul intended. Not once does Romans describe heaven as a place where you go when you die. Not once does Romans describe the wrath of God as going to hell when you die. Not once does Romans describe the goal of salvation as being going to heaven. These are later theological concepts that are not on Paul’s mind. If we want to hear what Romans says, we need to stop coming to it with our questions and start going to it with an open mind, ready to hear what God might have been saying through Paul.

The Message of Romans

So what is the purpose of Romans? It is to show that God is just or righteous in saving Gentiles from the judgment described above. I used to read the words, “the righteousness of God is revealed” (Romans 1:17; 3:21), as speaking of an imputed righteousness, as if it was saying, “now we can see where we get righteousness from – God.” It wasn’t until I taught a seminary course on Romans that I noticed that Paul spells out what he means in Romans 3:5: “if our unrighteousness serves to reveal the righteousness of God, what shall we say, that God is unrighteous to inflict wrath on us?” The context there is a quotation of Psalm 51:4, which says that God is “justified” in judging David. This is not about how David can be righteous, but a question of how God can be righteous in punishing or rewarding David as he sees fit. As Paul says later in Romans, God “has mercy on whomever he wills and hardens whomever he wills” (Romans 9:18). Romans is dealing with a question of theodicy: is God good? If many of the people God made promises to (Israel) are rejecting God’s reign, and many who have never worshiped God (the Gentiles) are receiving it, is that fair? How should people understand the differing responses to Jesus among Jews and Gentiles? This is the question Romans addresses from beginning to end. In the process, Paul says some things about salvation being by God’s grace, but he is not talking about how to get saved; he is talking about how to think about God’s actions among Jews and Gentiles. Paul is justifying God’s activity of saving many Gentiles and judging many Jews in his day.

Of course, even if Romans was written to address a different question than the one we are asking, the book still has things to say about our questions, but there are a few things we should keep in mind:

- It is important to read Romans not on our terms, but on Paul’s terms. We can’t just listen to the book for what we want to hear and not let it challenge us about questions we weren’t even thinking about.

- We need to remember that Paul uses terms very differently than we use them. Just as “salvation” meant something different to Paul than it means to us, so do other key words: “faith,” “believe,” “works,” “glory,” “death,” “eternal life.” We need to be careful not to assume that Paul is using those words the way we’ve used them.

- We need to pay attention to the context of the verses we quote. By quoting Romans 3:23; 6:23; 5:8; 10:9-10 and others apart from the larger argument they are part of, we start hearing different things in those verses than what Paul is teaching.

The Verses in “the Romans Road”

Let us consider the four points of Romans Road evangelism and note how differently we are reading these verses than Paul intended them.

Are We All Sinners? (Romans 3:23)

“All have sinned and fall short of the glory of God” (Romans 3:23, ESV).

We make two errors when we quote Romans 3:10 or Romans 3:23 in the context of “the Romans Road.” First, we read Paul more individualistically than he intends. Paul’s point is that all – Jews as well as Gentiles – have sinned and fall short of the glory of God. That’s why the fuller quote is “For there is no distinction, for all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God. … Then what becomes of our [Jews’] boasting? It is excluded. … Or is God the God of Jews only? Is he not the God of Gentiles too? Yes, of Gentiles too, since God is one—who will justify the circumcised [Jews] by faith and the uncircumcised [Gentiles] through faith” (Romans 3:22-30). We hear the word “all” as “every person,” whereas what Paul is saying is “Jew and Gentile alike.” The point being made here is not an individualistic salvation point, but a national pride point.

Second, we read “fall short of the glory of God” as if it means that God is judging us for not being as glorious as he is, something that we were never intended to be. It might be better to think here in terms of the image of God. Like the nations [Gentiles], Jews have fallen short of being representatives of God’s glory. Their justification comes not from how well they have represented God, but “by his grace as a gift, through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus” (Romans 3:24). It is in Jesus that Jews (and Gentiles!) are finally able to bear the image and glory of God (Romans 5:2; 8:18-30).

The message of Romans 3:23 is that the playing field between Jew and Gentile is level (cf. Romans 3:9). What the Romans Road tries to make Romans 3:23 say is that we are all sinners. Now Paul knew as well as we do that nobody is perfect, but Paul never expected anyone to be perfect and neither did the Old Testament Law, which included rituals to deal with our imperfections. Romans Road evangelism gives people an improper view of what God expects and leads to unhealthy levels of guilt.

I have a friend who when asked how he is doing will always answer, “Better than I deserve.” He has taken Romans Road theology to its logical conclusion: we deserve the wrath of God rather than the love of God. Not only is this not what Romans 3:23 is saying, but it opposes what Paul is arguing in Romans. Paul argues that God “will repay each person according to his works: to those who [persist] in doing good … he will give eternal life, but for those who are self-seeking, … there will be wrath and anger” (Romans 2:6-8). By misreading Romans 3:23, we have made Paul’s argument out to be that we all deserve hell, when Paul’s point is more that God is just in treating Jews and Gentiles the same as each other. In Paul’s view, many Gentiles deserve God’s commendation rather than his judgment (Romans 2:13-16, 26-29).

Do We All Deserve Hell? (Romans 6:23)

“For the wages of sin is death, but the free gift of God is eternal life in Christ Jesus our Lord.” (Romans 6:23, ESV).

As a young Christian, I often used Romans 6:23 to explain the gospel. I didn’t need the full Romans Road; all the aspects of the Romans Road gospel could be found in this verse: sin, wages, death; God, gift, eternal life in Jesus, Messiah and Lord. I would explain that we have all sinned and that death is what sinners have earned just as wages are what an employee has earned. I would explain that eternal life is not what we deserve but is a “free gift,” and that it can only be obtained by making Jesus Lord, thereby surrendering to him.

The first thing that made me realize that this interpretation of Romans 6:23 is problematic is when I started studying the Old Testament Law. There were sins that lead to death and sins that do not lead to death. I was surprised to discover that sacrifices could be made only for sins that do not deserve death; there was no sacrifice for sins punishable by death (Exodus 21:12-14; Leviticus 4-5; Numbers 15:30; etc.). This severely challenged my view that sacrifices were substitutes. I had always thought that the wages of sin is death, but God allows an animal’s death to be a substitute for the person’s death. That idea is foreign to Scripture. Sacrifices were offerings to restore one’s relationship to God, not substitutes for one’s own blood.

So why does Paul say the wages of sin is death? In context he is discussing the difference between Adam’s sin and Jesus’s free gift. That is how this section of Romans begins. Paul says in Romans 5:12-21 that death came into the world through Adam’s sin. “Therefore, as one trespass [Adam’s sin in the Garden] led to condemnation for all men [mortality/death], so one act of righteousness [Jesus’s sacrifice] leads to justification and life for all men [Jew and Gentile].” (Romans 5:18, ESV). Paul expounds this idea through the next three chapters of Romans. In Romans 6, Paul is calling people to no longer live in Adam’s sin, but to “present yourselves to God as those who have been brought from death to life” (Romans 6:13). Romans 6:23 sums up the argument so far: the wages of [Adam’s] sin is death [mortality], but the free gift of God is eternal life [by living in] Christ Jesus our Lord.”

Romans 6:23 says nothing about us deserving hell or judgment. It is a call to live in Christ rather than in Adam, to live in the Spirit rather than in the flesh. That’s why Romans 7–8 contrasts the flesh and the Spirit. “For to set the mind on the flesh is death, but to set the mind on the Spirit is life and peace” (Romans 8:6). To make Romans 6:23 out as if it were bad news about what someone who commits a single sin deserves is to miss Paul’s argument. It is not as if because we fail to be perfect, we deserve a spiritual and eternal death. The Torah made it clear that most failures do not result in death. The point is that we are mortal because sin entered the world through Adam, but immortality is now available through Jesus.

Romans Road evangelism has the danger of making salvation out to be an intellectual transaction: you really deserve hell, but God is so gracious he’ll give you heaven instead if you pray this prayer. Romans 6:23 instead teaches that there are two paths: one, the way of Adam, leads to death, and the other, the way of Christ, leads to life. Watch that you walk the path of righteousness rather than the path of sin.

Has God Freely Offered Heaven Instead of Hell? (Romans 5:8)

“But God shows his love for us in that while we were still sinners, Christ died for us” (Romans 5:8, ESV)

The third part of the Romans Road is stronger than the first two. The only dangers here come in (1) missing the Father’s love here and (2) making this about escaping hell and going to heaven. Some evangelistic proclamations make it out as if God the Father is the angry judge waiting to punish sinners, and Jesus is appeasing his wrath. I have addressed this in my post “Did Jesus Experience the Father’s Wrath?” In short, God so loved the world that he gave his only Son. Or in the words of this passage, “God shows his love for us.” This is why it doesn’t work to say we are “just sinners saved by grace.” Biblically we are God’s children, predestined to bear his image and glory (Romans 8:29-30). We are instruments of God’s love through and through. Presentations of the Romans Road that emphasize the Father’s love here are good. The similar Four Spiritual Laws also has this strength in that it begins with God’s love.

But there is also the danger of making this about heaven and hell, which it is not. Romans 5–8 is looking forward to “the revealing of the sons of God” (Romans 8:19), which will transform creation. Romans has a very this-world focus, and Christ’s death for us is not so we can go to heaven when we die but so we can live a new life and redeem the whole earth (Romans 8:19-23). We look forward to the return of Jesus and the final defeat of all evil on earth (Romans 11:26). A better reading of Romans is one that looks to the transformation of earth rather than one that looks forward to a disembodied state after death.

Is It Really About a Confession of Faith? (Romans 10:9-10)

“If you confess with your mouth that Jesus is Lord and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved. For with the heart one believes and is justified, and with the mouth one confesses and is saved.” (Romans 10:9-10, ESV)

In the twentieth century, evangelism became more and more about bringing people to a moment of decision, the moment when they would be “born again” (a misunderstanding of John 3:3, 5, and the same misunderstanding that Nicodemus himself makes), the moment when they would be “saved” (though Paul speaks of salvation largely as a future act, Romans 5:10, etc.). And what better passage to emphasize making a decision in your heart and confessing it with your lips than Romans 10:9-10? The irony is that Paul is doing something very different in Romans 10, and biblically, confessions don’t mean as much as we make them out to (cf. Matthew 7:21-27).

Romans 10 is difficult to understand, and I have only recently begun to feel like I see where Paul is going here. Paul uses a series of passages in Romans 9 (Genesis 21:12; 18:10, 14; 25:23; Malachi 1:2-3; Exodus 33:19; 9:16; Isaiah 29:16; 45:9; Hosea 2:23; 1:10; Isaiah 10:22-23; 1:9; 28:16) to explain why Israel is largely failing to obtain salvation.

Romans 10:9-10 is not a major point Paul is making, but a transition comment. Paul has just quoted Deuteronomy 30:14 (“The word is near you, in your mouth and in your heart”), and he is using it to make the point that Gentiles could receive this word as well. Look at the next three verses: “For the Scripture says, ‘Everyone who believes in him will not be put to shame.’ For there is no distinction between Jew and Greek; for the same Lord is Lord of all, bestowing riches on all who call on him. For everyone who calls on the name of the Lord will be saved” (Romans 10:11-13, ESV). The argument is very similar to the one we find in Romans 3:21-31, but here the point is that what is needed is something Gentiles as well as Jews can do, as long as Jews faithfully proclaim the message to Gentiles (Romans 10:14-17). This is what Paul is doing, proclaiming to Gentiles the gospel of God’s reign being established in Jesus’s resurrection and ascension. That makes Paul’s ministry a fulfillment of Isaiah 52:7 (Romans 10:15). Romans 10:9-10 is not about what we must do to be saved, but about how you don’t need to do Jewish things to be saved. Many who do Jewish things have missed out on salvation altogether (Romans 9:31; 10:3).

Often Paul’s message about not needing to do works of the law (Jewish things) gets misinterpreted in evangelical preaching to mean that we are not rewarded for our good works, but we have already seen in Romans 2:6-11 that Paul says we are rewarded for our good works. Evangelical preaching tends to make everything about the moment of decision and praying the sinner’s prayer, but to Paul it is about keeping in step with the Spirit (Galatians 5:16-25), about walking in Christ rather than in Adam (Romans 6:1-23), and about working out our salvation with fear and trembling (Philippians 2:12-13). By omitting verses like these and selecting verses that can be read out of context to promote the Romans Road gospel, we preach a somewhat different gospel than the one the Bible presents.

Conclusion

Romans is not a roadmap to heaven. It is not about how to escape hell. Romans is assurance that God knows what he is doing and that we should therefore obey him. As Paul says at both the beginning and the end of the letter, he wants “to bring about the obedience of faith” among all nations (Romans 1:5; 16:26). The good news or “gospel” is the announcement that Jesus is on the throne. The result of this announcement shouldn’t be that we all grab a “Get out of hell free” card, but that we should submit to his Lordship and walk in Jesus now rather than in Adam. That is the true Romans road.

The popular Romans Road evangelism flattens this and makes Romans about teaching that we all deserve hell but can get to heaven by saying, “Lord, Lord.” The true teaching of Romans is that sin leads to death, righteousness leads to life, and by being more like Jesus we can escape enslavement to sin (Romans 6:5-14) and live that righteousness that leads to life. We choose to offer our bodies as living sacrifices not because we want to escape hell, but because we can … and because it is what we have always wanted (Romans 7:16-20).

A popular reading of select verses from Romans gives improper levels of guilt, an emphasis on our intellectual beliefs, and a desire to escape hell and obtain heaven. A good reading of Romans gives us excitement about who God is and what he is doing, an emphasis on our actions as being actions appropriate to the reign of God, and a desire to transform the earth and bring about the new creation. One approach is popular; the other is biblical.